` Now, I had actually e-mailed this text to myself on Friday, though today was the first time I've been able to access my blogger account (due to technical difficulties), so I apologize for the length of time it took to put this up:

` These 'Quasi-Noci-Notes' are actually from a historical - rather than a science - book called Hope is the Thing With Feathers by Christopher Cokinos. (The title comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson.)

` It is, as you may have guessed, about birds. More precisely, it is a book full of very eloquent and loving obituaries for certain species of North American avians: The Carolina parakeet, the Ivory-billed woodpecker, the heath hen, the passenger pigeon, the Laborador duck, and the great auk.

` …As you may know, times have changed for the better now that it is clear that the Ivory Bill has survived in Arkansas – and therefore does not truly belong in Cokinos' book. Though it once lived in the south, from Texas to Missouri to southern Ohio, most Ivory-bill habitat has been destroyed - which is probably the main reason for its sixty-year disappearance from human detection.

` Much of this discovery has been written about recently, although I have been slow to catch any of it. It just so happens that I have a few tidbits from recent magazine articles, including this one from the humorous Steven Mirsky of Scientific American:

` …I imagined that it’s probably in the best long-term survival interests of any species to keep the word ‘ivory’ out of its name. I therefore mused that the ivory-billed woodpecker should henceforth be known as the cheap-Formica-billed woodpecker. You know, for its own good.` There’s even a Skeptical Inquirer article by Benjamin Radford about the Ivory-bill and the way some people use its rediscovery as some kind of evidence for the existence of Bigfoot. Of course, those are two entirely different matters:

` The Ivory-billed woodpecker has been known to science for hundreds of years. Nobody has ever doubted that it is a real species. On the other hand, Bigfoot was invented in the 1950's - and if you’d like to read more about the history of Bigfoot, be my guest!

` The point of the article is this: The existence of a small population of a small species that we are already familiar with from earlier interactions, records and specimens does not mean that thousands of large - and therefore easier to spot - creatures of which no real evidence has ever been produced also exists.

` Plus, Bigfoot has only been reported since the fifties, beginning with a popularity stunt in the Canadian tourist trap of Hot Springs. Hello? ` Furthermore, a team of researchers that have taken masses of video and audio recordings in what is known as ‘Bigfoot territory’ have not yet found anything large and hairy that we don’t already know about.

` But I digress - this post is meant to be about the Ivory-bill ‘obituary’ of Cokinos’ book. No longer known as a proper obituary, however, it is still informative. Without further primates, beakers, or oroblancos, the chapter begins:

` Campephilus principalis, the Principal Lover of Grubs: The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, splendid recluse of the swamp.` As wonderful a description as this is, there is thankfully no longer any need to imagine it for some lucky Surveyors of All That Flies In Ivory-Bill Country. ` Such a proud bird this was, Cokinos goes on, that it shone from a famous description by Alexander Wilson. This man, originally from Scotland, once went searching for birds to paint for a book called American Ornithology, published in a set of volumes between 1808 and 1814. He wrote these words – paragraphing added by myself.

` Two of its nicknames announce the awe that this bird inspired –the Lord God Bird and King of the Woodpeckers. Observers impressed with the huge Ivory-bill would blurt, “Lord God!” For the Ivory-bill measured nearly two feet long, beak to tail, with an imposing wingspan of two and one half feet and a bill about three inches long and one inch wide at the base….

` Brightly yellow-eyed and jittery, the Ivory-bill appeared vividly strange, nearly Mesozoic, as it pounded and drilled the rotting trees of shadow-wet forests and jerked its long, white-billed head this way and that, as if it were the alert guardian of the sloughs. The Ivory-bill conveyed a manic glory as it hopped up and down the sides of cypresses and hackberries or launched off into flight. Upon seeing an Ivory-bill for the first time, one naturalist wrote that he felt “tremendously impressed by the majestic and wild personality of this bird, its vigor, its almost frantic aliveness.” This, the King of the Woodpeckers.

` The plumage seemed elemental: black bodies with white stripes stretching from the side of the head along he neck and down the back; when the bird perched, a patch of white on the wings’ trailing edge showed like a knight’s bright culet. The female’s recurved crest displayed only jet-black, while the male sported a crest that gleamed in the sunlight shafting through the forest canopy….

` The first place I observed this bird at, when on my way to the South, was about twelve miles north of Wilmington in North Carolina. There I found the bird from which my drawing was taken. This bird was only wounded slightly in the wing, and, on being caught, uttered a loudly reiterated and most piteous note, exactly resembling the violent crying of a young child; which terrified my horse so, as nearly to have cost me my life.` Unfortunately, the woodpecker not only died in a hotel room as the subject of an illustration, but a fairly mediocre one! Double tragedy!

` It was distressing to hear it. I carried it with me in the chair, under cover, to Wilmington. In passing through the streets, its affecting cries surprised every one within hearing, particularly the females, who hurried to the doors and windows with looks of alarm and anxiety.

` I drove on, and on arriving at the piazza of the hotel, where I intended to put up, the landlord came forward, and a number of other persons who happened to be there, all equally alarmed at what they heard; this was greatly increased by my asking, whether he could furnish me with accommodations for myself and the baby. The man looked blank and foolish, with the others stared with still greater astonishment.

` After diverting myself for a minute or two at their expense, I drew my Woodpecker from under the cover, and a general laugh took place.

` I took him up stairs, and locked him up in my room, while I went to see my horse taken care of. In less than an hour, I returned, and, on opening the door, he set up the same distressing shout, which now appeared to proceed from grief that he had been discovered in his attempts to escape.

` He had mounted along the side of the window, nearly as high as the ceiling, a little below which he had begun to break through. The bed was covered with large pieces of plaster; the lath was exposed for at least fifteen inches square, and a hole, large enough to admit the fist, opened to the weather-boards; so that, in less than another hour, he would certainly succeeded in making his way through.

` I now tied a string round his leg, and, fastening it to the table, again left him. I wished to preserve his life, and had gone off in search of suitable food for him. As I reascended the stairs, I heard him again hard at work, and on entering, had the mortification to perceive that he had almost entirely ruined the mahogany table to which he was fastened, and on which he had wreaked his whole vengeance.

` While engaged in taking the drawing, he cut me severely in several places, and, on the whole, displayed such a noble and inconquerable spirit, that I was frequently temped to restore him to his native woods. He lived with me nearly three days, but refused all sustenance, and I witnessed his death with regret.

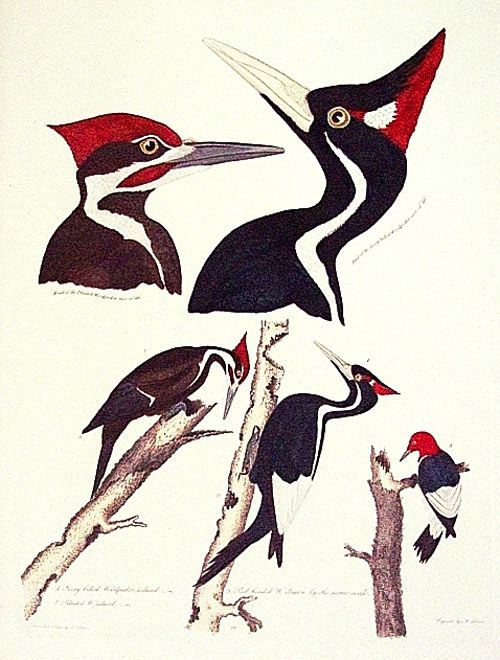

` (The other birds pictured are the pileated and red-headed woodpeckers.)

` The species continued to decline throughout the 1800s until it was pronounced extinct. However, in 1924 that all changed: In Florida, a guide named Morgan Tindle pointed out a bird’s nest to Arthur Augustus Allen, a distinguished Cornell University ornithologist.

` Two Ivory-bills lived... there! Sadly, when Allen and his wife, Elsa, briefly left the nest, two taxidermists shot both birds! He bemoaned this tragedy and understandably wondered if they had seen the only pair left in the whole world.

` Searches for the Ivory-bill continued to turn up nothing until April of 1932, when a Louisiana state legislator and attorney named Mason D. Spencer, shot one in Madison Parish! The officials at the conservation department constantly scorned verbal reports of the bird - joking that the moonshine must be really strong in the area - until they saw Spencer’s specimen!

` Soon enough, Audubon Society president T. Gilbert Pearson and Ernest G. Holt (who was then the director of Audubon’s Refugees Program), came to Madison Parish in order to investigate the region.

` Between May 12 and 17 in 1932, they observed Ivory-bills on land owned by the Singer Sewing Machine Company. So much was unknown about the habits of the reclusive bird that this was an incredibly lucky chance to learn more.

` It wasn’t long before Arthur Allen and a team from Cornell deigned to do something more enlightened than shooting what they studied. They were trying out something new - touring the country in order to record the birds instead of kill them. Naturally, they set out to film and record the voice of the majestic woodpecker, as well as to study how Ivory-bills live in order to figure out the best method of preservation.

` Along their bird-recording tour of the country, the scientists found themselves in Mason Spencer’s law office, where he talked about the Ivory-bill with enthusiasm, using the local word for them. The curator of ornithological specimens at Cornell, Dr. George Miksch Sutton, recalled Spencer saying: ‘Man alive! These birds I’m tellin’ you all about is Kints! Why, the Pileated Woodpecker’s just a little bird about as big as that.’ (Holding fingers close together) ‘And a Kint’s as big as that!’ (Spreading his arms far apart.) “Why, man, I’ve known Kints all my life. My pappy showed ‘em to me when I was just a kid. I see ‘em every fall when I go deer huntin’ down aroun’ my place on Tinsaw. They’re big birds, I tell you, big and black and white; and they fly through the woods like Pintail Ducks!’

` Indeed, ivory bills would indeed look as sleek and pointy-tailed as a Pintail while flying. This description convinced the Cornell team that Spencer was indeed familiar with the birds and could be trusted.

` Next, in April of 1935, they went to the swamp of Singer Tract, though the trucks quickly became mired in the recent March rainfall. Sutton commented that the trail to woodsman J. J. Kuhn’s cabin was ‘practically a lake’, though they managed to get through on a mule-drawn wagon.

` They searched everywhere for the bird, amazed by the foot-long pieces of wood and bark they had chipped off while feeding. At one point, Kuhn, swearing that he’d heard the bird while the men walked across a fallen Cypress, finally saw one: He grabbed Sutton and pointed him in the right direction – they nearly fell as he said; ‘It flew from its nest, too, doc! What do you think of that! A nest! See it! There it is right up there!’

` Sutton hadn’t gotten a good look at the bird, but this nest… yes, that was something! They held onto each other’s arms and shirts, giddy, laughing and dancing at the whole prospect, while trying not to fall into the briars and muck. The other two people on the scene, Arthur Allen and graduate student James Tanner, quickly caught this bug of joyousness. Soon enough, the men were all shushing one another – they had finally heard the call of the Ivory-bill.

` Incidentally, just afterward a tree had fallen in the woods and scared them half to death.

` What a great time that had been! The mosquitoes were not yet out, plus they had managed to take photographs of the birds at their nest. It wasn’t long afterward that the team loaded up their equipment and took moving pictures as well as audio recordings in a small area they called Camp Ephilus. (Get it?) This is where Tanner, Allen and his assistant, Dr. Peter Paul Kellogg, bivouacked, studying the animals for five days, ending on April 14.

` The men watched each morning when, at 6:30, the male (whose duty it was to spend the night incubating the eggs) “Tapped on the inside of the nest hole,” then “grew more impatient [and] stuck his head out,” calling “a few ‘yaps’ or ‘kents’ in no uncertain tone.” When the female finally arrived, “a little intimate conversation then ensued and she entered.” The only foreboding note to this otherwise fetching daily ritual happened when the male would spend several minutes preening and scratching,” as if he were infested with mites,” Allen wrote.` Until 4:30 each afternoon - when the male entered the nest for his long 14-hour night shift - the parents alternated between incubating and feeding in two-hour intervals. James Tanner described in wonderful detail the “regular ceremony” that usually took place when a shift conclused:

` One would fly or climb to the entrance and signal the other by calling or pounding. We occasionally heard the setting bird answer by pounding on the inside of the cavity. It would flip out of the hole and catch itself on the outside of the tree beside its mate, and the pair would then exchange a low, almost musical call that had a conversational quality, often given with their bills pointed upward.` Unfortunately, the Cornell team left after this time, just at the beginning of the second year of what is now referred to as the Dust Bowl. In fact, April 11 of that year was Black Sunday, a day when black dust got into every conceivable crevice – including the inside of lungs, sometimes resulting in death.

` What had become of the Ivory-bills was scandalous: They had left their nest, and when the cavity was examined it was found littered with woodchips and eggshell, all swarming with mites. However, Allen saw later that day another nest with parents feeding their young. Unfortunately, that also failed and yet no mites were discovered in the cavity afterwards.

` After this, in the Singer Tract, James Tanner went on studying Ivory-bills passionately, counting six of them there. Then, he went looking for more C. principalis in other potential locations in North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. Though the accounts of many people there were credible, his search was in vain.

` So, he stuck with the Singer Tract birds.

` While discouraged by rain, the birds were otherwise “quick and vigorous, almost nervous,” Tanner wrote. “When perched and alert, they have a habit of swinging the body quickly from one side to the other, pivoting on the tail pressed to the tree, pausing to peer back over the shoulder, then swinging back and looking over the other shoulder, at each quick swing flirting [sic] the wings.” The Ivory-bill seemed to glory in its own body, in brisk, keen movements.’` In each six square miles, only two Ivory Bills could be found – however, one square mile could harbor 21 Red-bellied woodpeckers, and 6 pairs of Pileateds. Life was tough for the Ivory-bill because it scaled the bark of trees to get at its most precious food items - grubs. Unfortunately, most of the trees in the Singer Tract were too small for a roosting hole as well as much in the way of infestation (and thus food).

` Unfortunately, as the Ivory-bills favored the grubs from trees that had been dead for only two or three years, such grubs were quite scarce. Therefore, any place where the trees were in danger of being cut down, the woodpecker's future would be in danger.

` On top of this problem, there were plenty of people shooting the birds, profiting from their bills or stuffing their skins for display.

` And then, the unthinkable happened: The Singer tract was logged. While the timbermen were careful to girdle the trees – to provide grubs for the Ivory-bills – and to only cut down certain trees without clear-cutting, and to use animal carts, this was still a very bad thing for the birds.

` In 1934, there were seven known Ivory-bill pairs and four young. In 1939, only one pair, one young bird and three males remained. James Tanner saw the Singer birds for the last time in 1941. In March 1942, he wrote:

There is little doubt but that complete logging of the tract will cause the end of the Ivory-bills there, and since the surrounding country is young second-growth forest and cultivated lands, it will doom the woodpeckers to a vain search for suitable food and habitat. Discussions are being carried on with officials of the company controlling the tract to determine what might be done for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker….` Even John Baker (president of Audubon) had appealed to Franklin Roosevelt (president of the United States), and before he knew it, the directors of the Forest Service, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service and War Production Board were all pitching in!

` Governor Sam Jones of Louisiana pledged him two hundred thousand dollars: Then he and three other governors - Prentice Cooper of Tennessee, Paul B. Johnson of Mississippi and Homer Adkins of Arkansas - wrote to Chicago Mill, asking them to not interfere with the Ivory-bill, as it would surely go extinct. (Considering that the loggers were German POWs, nobody would lose their jobs for lack of trees to cut down!)

` At the meeting between the chairman of the board of Chicago Mill and Lumber, John Baker, the conservation commissioner, the refuge director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (and their attorney), chairman James F. Griswold stated that; “We are just money grubbers. We are not concerned, as are you folks, with ethical considerations.” The rest on his side of the matter seemed just as indifferent.

` Baker sent Audubon staff – and future Nature Concervancy president – Richard Pough to the Singer Tract each day from December 4, 1943 to early 1944. He wrote; ‘So far, no I-Bs. It is sickening to see what a waste a lumber company can make of what was once a beautiful forest. Watched them cutting the last stand of the finest sweet gum on Monday. One log was 6 feet in diameter at the butt.’

` Even Chicago Mill’s own local attorney – Henry Sevier – was all for the preservation of the wild land. Pough even stayed at Sevier’s hunting camp in the woods. Then one day, in the icy rain, he found a lone female – one that Baker had once seen. She was feeding on the second-growth woods, as she wouldn’t fly across the logging railroad or the cutover land to find older trees.

` Pough wrote to Baker: ‘Can’t help feeling that mystery of I-bs disappearance is not as simple as Jim’s report might lead one to believe. I wonder if the bird’s psychological requirements aren’t at bottom of matter rather than it being just a matter of food.”

` Indeed – sometimes animals will not cross a barrier such as a change in landscape and so become isolated populations. This strong tendency has, in fact, been known to create distinct species, and can be used to keep animals confined within certain areas of zoos.

` Wildlife artist, Don Eckelberry had caught wind of this Ivory-bill news and managed to get to the spot during the floods of April. For two weeks, he followed that lone female around, painting her.

` At the same time, he got to watch the U.S. Army guards force the POWs to cut down the trees and load them onto trains bound for Tallulah, noting the fact that they were “incredulous at the waste – only the best wood taken, the rest left in wreckage.”

` And for what? According to Chicago Mill’s official John R Shipley; “The Tallulah Plant was so busy making… chests for supplying the English army with its tea that they had a regular production line which ended in 3 box cars sitting side by side on the railroad siding tracks.”

` Tragedies upon tragedies!

` After the destruction of the Singer Tract, the birds continued to be sighted in the south by respected naturalists and amateur birders alike, as well as audio-taped and photographed. Still, nothing could be confirmed as to the authenticity of such records – it could all easily be a hoax.

` Even as late as 1987, Jerome Jackson – one of the world’s authorities on Ivory-bills - said that he and a student had heard what could only be described as that very species. They had listened to it for several minutes in a forest north of Vicksburg, Mississippi – though they never did catch a glimpse of it. Jackson wrote that loggers had since cut that forest down. Then, in the 1990s, Jackson heard of some reports from Florida that could not be easily dismissed.

` Other fairly credible sightings have come from other states as well as Cuba. In 1980, the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge was established over the land that had once been the Singer Tract. One of the managers, Kelby Ouchley invited Tanner to the part that had been Singer Tract. Strangely and horrifyingly, Chicago Mill and Lumber happened to be logging in the refuge at that time.

` Said Ouchley; “The day he came we could see some of the old nesting areas were just cleared [again]. It was a pretty grim situation… midnight phone calls telling us that ‘dozers had moved in and were clearing. There were [court] injunctions.”

` In the last part of the chapter, Cokinos writes about his own experiences as he grasped at ghosts. He strides into the new growth of the wildlife refuge, near to where an Ivory-bill named Mack Bayou Pete had roosted in 1938. Tanner had recalled Pete:

[He] was hard to find, and once found was soon lost. Restless as a blue jay, Pete would dig out a few borers, pound and call loudly, then wing through the tree tops to some distant part of his domain, leaving the earthbound watcher to plod over (and through) the forest floor in the same general direction with eyes scanning the trees and ears stretched wide to hear a distant kent.` Then, Cokinos plays the Ivory-bill sounds recorded by the Cornell scientists… And at the same time, I am listening to part of that recording. I think it sounds rather like a very staccato: Ep! Eep-ep! Eep! Eep! Eep! Eep! Eep! Eep! Eep-ep!... There is also some drumming and what seems to be two birds calling to one another.

` Says Cokinos: ‘Some psychologists, scientists and activists have written about the parallels between familial grieving and ecological grieving, comparing the loss of a treasured place or species to the loss of a loved one. If the comparison rings true, and it does for me, then we must find ways to grieve well. We must confront loss rather than deny it and, in doing so, nurture the energies to cope with the difficulties of loving a world we have systematically diminished.’

` I can’t claim to really understand how Cokinos feels, though I trust that his nostalgic, poetic drama is probably not even a sign of eccentricity – in fact, I sort of understand where he’s coming from:

` At the beginning of the book, he describes observing (to his surprise!) two nanday conures – a type of green parakeet – being chased by an osprey through marsh in Kansas. These birds, having evidently escaped from humans, looked - to him - very alien and out of place in this habitat. That is, until Cokinos discovered that the waterways in Kansas were once home to America’s own green parakeet!

` I admit – when I had first learned that Carolina parakeets were once a native species in the country in which I was raised, I felt scandalized that no one had ever notified me, as well as upset by the fact that bird books never seemed to mention them!

` ‘Hey,’ I’d inanely protest to myself. ‘They were real birds, too! Just because we killed them doesn’t mean we have to forget that they ever existed! What kind of sense does that make?’

` Such was not the case when the species was abundant. Indeed, the NativeAmericans revered them. In addition, the memoirs of a settler’s daughter, Sarah Dyer, read that in the spring of 1853, she saw ‘lots of wild parroquets’ in Kansas. At this time, the parakeets were more or less taken for granted.

` But what about as time went on? Cokinos gives an example of an old man recalling life in the early 1900s of Florida. This man had believed that the parakeets foraging on his land were from Cuba, which is what his neighbors had told him.

` Was the Carolina parakeet being widely forgotten by then? How many people remembered that it had really belonged in their backyards and not some tropical land?

` Cokinos was quite dismayed of the fact that he personally knew more knowledgeable and experienced birders which did not even know about this species. That is why the first chapter of his book is entitled ‘The Forgotten Parakeet’.

` The point is, not only is it a tragedy when a species dies – at least when we're the ones who make it too difficult for them to carry on! - but when we forget the existence of that species altogether, that tragedy is compounded. Hence, Cokinos’ educational guide to remind others of experiences that bird enthusiasts of past times have had, and perhaps even the sense of mourning one has when they fall in love with something after it has already been destroyed.

` And here, I've passed some of that onto the World of the Internet. My hope is that some thought it was interesting.

4 comments:

Forgive me if I'm not making any sense... but wouldn't it have been more productive to write about species that we are more prone to forgetting because they are extinct?

` Uhhhhmmmm... well, I figure that since Ivory-bills have been prominent in the news, they may attract more attention to this subject.

` Yeah, that's it!

` Also, it's at least remotely possible that the video and the audio recordings do not really show Ivory-bills, and that it was a sheer coincidence that both seem to confirm the animal's existence!

` ...So maybe they really are extinct! Ha!

Actually, I just heard that it's quite possible there really aren't any left!

` Right you are. Well, then, your first statement seems to have been nullified!

` And this bird will stick in people's memories because it's been in the news!

Post a Comment